The best thing history gives us is the enthusiasm it arouses.

Johann Goethe

Taking this opportunity, once again, I want to express my deep respect and gratitude to our friends from Russian Majolica . The reviews they publish are incredibly interesting, they stand out from the variety of feature articles filled with technological data, dry statistics or historical information, and a special spirit of storytelling. This is not the first time I catch myself thinking that after reading yet another material, I have a persistent desire to “Google” additional sources of information on the Internet, become more familiar with the topic, and put it aside in my mind.

One of these topics for me was a series of articles devoted to a unique ceramic material - pyrogranite. This material, the prototype of modern porcelain stoneware, is unique in many ways, including the fact that despite its more than century-long history of production and widespread use, little is still known about it.

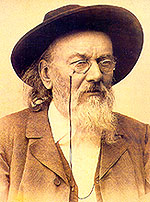

The invention of pyrogranite is credited to the Hungarian industrialist Vilmos Zsolnay, who took over the family manufacturing enterprise in 1868.

The invention of pyrogranite is credited to the Hungarian industrialist Vilmos Zsolnay, who took over the family manufacturing enterprise in 1868.

His interest in innovation in the field of architectural and artistic ceramics allowed Zsolnay Porcelánmanufaktúra Zrt (Zsolnay Porcelain Manufactory) to become the largest ceramic manufacturer in Austria-Hungary within a short period. By 1898, 23% of all ceramics in the empire were produced at the Zsolnay factory in the city of Pécs. The company received orders from reigning houses and ruling circles. There is not a single city in Central Europe where there would not be a building tiled with ceramics from the Zsolnay factory. In addition, Vilmos Zsolnay in the 1890s, based on the experimental results of Vince Wart and Lajos Petrik, experimentally developed a unique technique for reduced lustrin, the so-called “eosin”. Eosin glaze inspired young applied artists (Sandor Apati Abt, Henryk Darilek, Sandor Hidashi Pillo, Lajos Mak, Geza Nikelski) to create decorative ceramics of independent sculptural value, often with symbolic meaning.

Vilmos' daughters Terez and Julia also took part in the design work.

They started out as self-taught artists, but very quickly reached the artistic level of applied art. Therese developed motifs of folk art and "lordly embroidery", and Julia designed in an orientalist style. She especially willingly turned to the Iznitsky (Ottoman-Turkish) and Japanese world of expressive means. Nothing was impossible for the enterprise - everything that could be produced from ceramics was made at the factory.

The invention of frost-resistant pyrogranite by the end of the 80s of the 19th century served as a new round in the development of European architecture. The special properties of the material were determined by high-temperature firing at 1200-1300 degrees. At these temperatures, ceramics are sintered to the state of glass and its water absorption approaches zero. In addition, the molding of products was carried out with powerful presses, which made it possible to achieve a high level of density of the clay mass, the unique composition of which made it very strong. Together with the invention of eosin glaze, this gave such an impressive result that this period in architecture can be called the time of the creation of functional art. The company in Pécs still exists and houses the Zsolnay Ceramics Museum.

It is surprising that around the same time, several thousand kilometers away in the town of Lystsovo, located on the left bank of the Msta River, Borovicheskiy district, Novgorod province, Prince Mikhail Golitsyn opened a factory for the production of refractory bricks and ceramics.

It is surprising that around the same time, several thousand kilometers away in the town of Lystsovo, located on the left bank of the Msta River, Borovicheskiy district, Novgorod province, Prince Mikhail Golitsyn opened a factory for the production of refractory bricks and ceramics.

And this plant would have been unremarkable among the dozens of industrial productions that appeared in the Russian Empire in the second half of the 19th century, if not for master Matvey Nikitin (in street style - Veselov) - the Russian inventor of a special refractory brick with amazing technical characteristics. hardness, water resistance, frost resistance. By mixing various samples of local clay, the master developed his own recipe for “fire granite”, which is superior in quality and price to foreign analogues. Here is the conclusion given to domestic pyrogranite by Nina Vasilievna Ageeva, who for a long time was in charge of the museum at the Borovicheskiy Refractories Plant:

“Products under the brand name “Pyrogranite” corresponded in their characteristics to the definition of clinker - an artificial stone of high strength, made from clay by firing it until the mass is completely sintered, but without vitrifying the surface. The most important property of clinker as a building material is its high resistance to mechanical and chemical influences. Pyrogranite was used as road, sidewalk and cladding products for building facades.”

The writer Vitaly Garnovsky in his story “Fire Granite” (1964-1965) tells in detail the history of this invention, describes the participation of “a man of the people” Veselov in the Paris World Exhibition in 1889, the stingy and narrow-minded Prince Golitsyn (who has nothing in common with his prototype, except for the title and surname), and the tragic death of Matvey Ivanovich, allegedly fired from the factory for obstinacy and intractability.

Probably, this story formed the basis of the legend about the hot-tempered and short-sighted prince, an unrecognized Russian nugget and invention, the secret of which disappeared into the darkness of centuries.

Nobody knows for sure how things really were, but here’s what A. Ignatiev writes about this in the newspaper “Delovye Borovichi”:

“The real events, of course, remained a mystery to us, but the memories of people who personally knew the master were preserved - these are the worker Dmitry Alekseevich Rusakov and the widow Evdokia Modestovna. According to these memoirs, Veselov previously worked in St. Petersburg “as a stone worker”, at “Pirogranite” - from the time the plant was built (“he laid the pipes himself”). He was about thirty years old at that time. “At first the plant was made of wood, then it was made of stone.” The laboratory in which pyrogranite was invented was a “separate little house with a forge.” They tried to burn a special mass of “pyrogranite” in this forge. It is unknown who invented this composition, but only two masters knew the secret: Veselov, who carried out the firing, and some “chukhna” who composed it (this second one went to his homeland after the closure of the plant). Dmitry Rusakov, who as a child brought lunches to Veselov, who was always at the plant, noted that pyro-granite was made using a special hydraulic press, which crushed pieces of pyrites and granite into a semi-dry, cement-like, grayish mass. The same Rusakov, who lived in the house next door to Veselov, reported that Prince Golitsyn and Matvey Veselov received medals for exhibiting samples at the World Exhibition in Paris, and also that the plant received an order “from England” for a large batch (“several million pieces") of pyrogranite tiles. One of the conditions in the contract was the absolute uniform color of the brick.”

The Borovichi Museum contains a tile with the autograph-stamp of Prince Vasily Golitsyn and with the text: “In memory of the first order - 1889.” According to the widow, the prince more than once asked Veselov to tell him the secret of production, but Veselov died, without telling anyone his secret.

But it seems that fulfilling the millionth order was impossible for other reasons: the invention of pyrogranite was based on the experimental mixing of various clay samples, the deposits of which could be very insignificant.

In this case, the “monocolor” of the products became a fatal clause in the contract, which led to the ruin and closure of the enterprise in 1893. After that, Veselov worked at the Kolyankovsky brothers’ plant (Nov plant on the Velgia River), in Parakhino (Krestetsky district) and at the Gavrilov plant in Poterpelitsy. He died “of consumption, at over forty years old” (he was returning from Migoloshchi, where he had laid stoves at school. He slept on the bare ground on the road and caught a cold). This happened only eight years after the closure of Pirogranit. The Veselovs had a relic of that glorious history - a silver medal from the Paris Exhibition. But after the death of the master, Evdokia Modestovna pawned her to the local moneylender Ivan Nikolaev, whose house was located on the right bank side of the city near the monastery, where she disappeared in a fire. At the end of the 1920s, the director of the Borovichi Museum, Sergei Nikolaevich Porshnyakov, after a conversation, purchased several products from the plant from the widow and her son-in-law K. Golumbovsky: half a polished brick, a tile made in Paris (with the profile of French President Carnot), a tile with a bas-relief depicting a medieval archer, small tabletop busts of Catherine II, as well as busts of Apollo and Venus.

It is known about the further fate of the Pirogranit plant that it was owned by Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich, who came to Borovichi for a regional exhibition. Subsequently, the owners of “Pyrogranit”, which from 1903 began to be called “Terracotta”, were JSC “Franco-Russian Pyrogranite”, engineer M. A. Rosten, railway engineer G. P. Starzhenetsky-Lappa (from 1903) and K. L. Wachter (since 1913). In 1919, the plant was nationalized, and it became part of the Borkombinat as plant No. 4 (in 1937 it was transformed into workshop No. 4).

As for the fate of Prince Golitsyn, in the future it had nothing to do with production. Once upon a time, the historian V.N. Tatishchev was jealous of the library of D.M. Golitsyn, which was considered the largest in the entire empire. Vasily Golitsyn turned out to be a worthy successor to this “book” tradition of his ancestor. In 1910, he became director of the Moscow Public and Rumyantsev Museums, and was an honorary member of the Russian Bibliographical Society, Tula and Pskov Provincial Archival Commissions. In 1918, he was invited to work on the Museum and Household Commission of the Mossovet, which was engaged in examining estates, personal collections, libraries and issuing safe-conduct to their owners. On March 10, 1921, Golitsyn was arrested, but was soon released without charge. From May 1921, he became the head of the art department of the State Rumyantsev Museum, which was soon renamed the State Library. V. I. Lenin. Vasily Dmitrievich died in 1926 in Moscow.

This is the story, what is true and what is not, decide for yourself.

I remember the old American wisdom - “a dollar to the one who invented it, ten to the one who made it and a hundred to the one who sold it.” Who knows, maybe Russian “fire granite” today would be a worthy competitor to traditional German clinker, if its fate had been different. But what happened happened. “History is in a hurry to record success, not the noble deeds of people,” it is difficult to argue with this statement, but perhaps the memory of the Borovichi pyrogranite indicates that this is not the end of history? Who knows...

The basis for writing the article was:

Materials from the site “Russian Majolica”

- “Two stories of pyrogranite” ;

- “Unique ceramics of Zsolnai” ;

- “Zsolnay Ceramics Museum in Pecs” ;

Article by A. Ignatiev “ On the history of the Pyrogranit plant in Borovichi”, website https://delbor.ru/

Review of “ Pyrogranit ” on the official page of the Museum of History of Borovichi and the Borovichi Territory in social media.

VKontakte network Free encyclopedia Wikipedia